Contemporary Ecology in the Work of Fawn Rogers

In a diverse practice spanning painting, sculpture, video, and multidisciplinary installation, the art of Fawn Rogers offers a dynamic and often searing approach to humanity’s engagement with the natural world. Frequently pitting beauty and harmony against ferocity and chaos, her work centers on the complex interactions between nature and industry, delving into themes of evolution, extinction, and the interstitial ironies that unite them.

At the forefront of Rogers’s current work is a focus on the ocean, specifically with an eye toward aquacultural perceptions and the implications of ocean-based commerce. In the two-channel video The World Is Your Oyster, bivalve mollusks––among the most susceptible bellwethers of oceanic intrusion––are vividly presented in varying states of peril and prestige. The pristine and over-harvested pearl is viewed in tandem with imagery of the full-scale destruction of the ocean floor, underscoring the prevailing concurrence of violence and consumption. This appropriation of the natural world is likewise explored in the painting series She Sells Seashells by the Seashore, in which the scallop-inspired grotto chair––a cogent symbol of the Anthropocene, emphasized by its associations with the history and gradual submergence of Venice into the Adriatic Sea––reflects the diverse conflicts and convergences among civilization and the natural world.

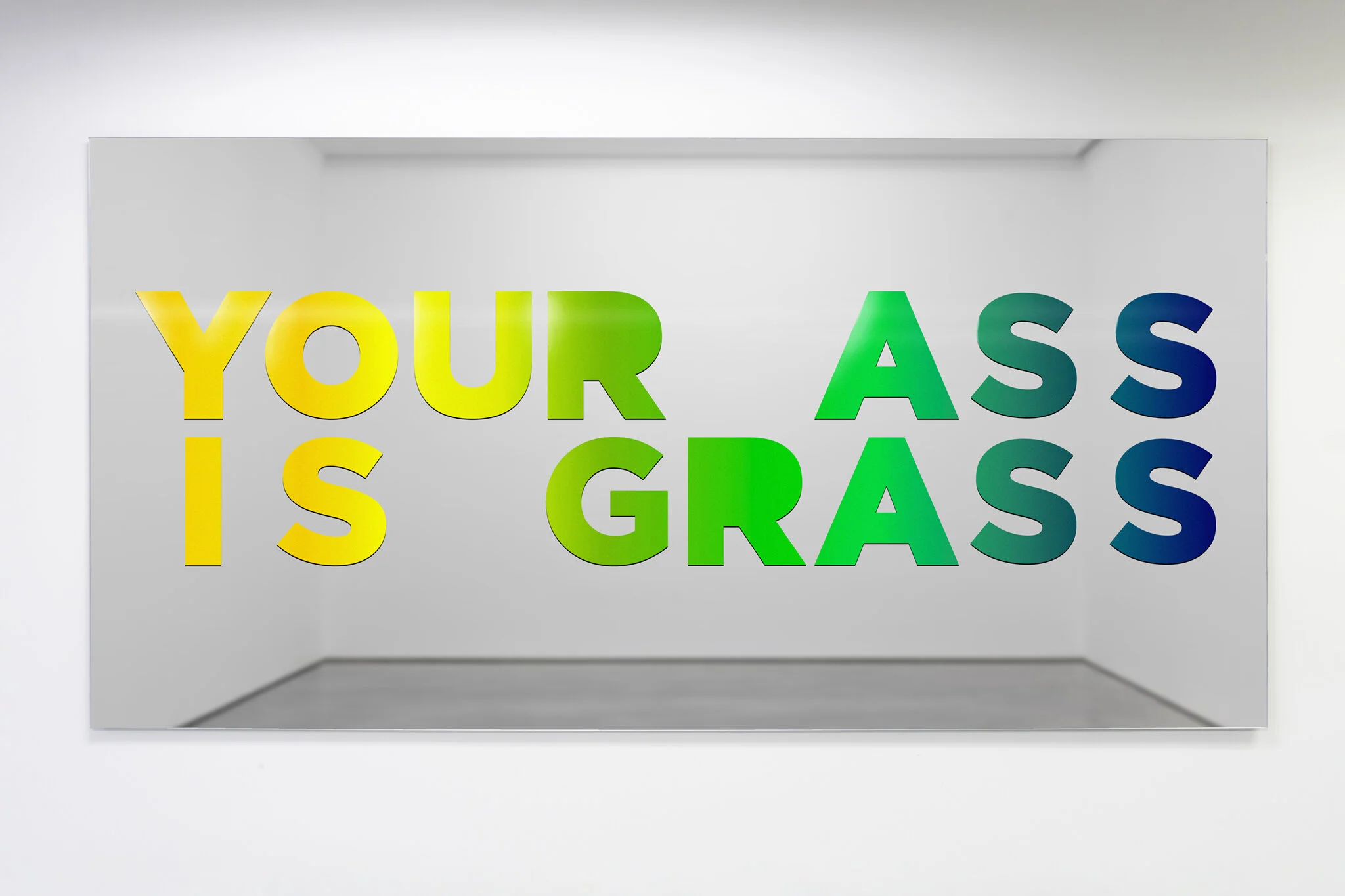

Throughout her work, Rogers leverages the artistic devices of humor, inquiry, and implication to engage a diverse audience. Arguably nowhere is this more true than in her exploration of ecological subjects, eclectically addressed in Fukushima Soil, Meteorites, and the Lipstick, as well as in the sharply contraposed reversals and jarring sensualities of Yes, Yes It Is Burning Me. From the playfully overt dynamics of Your Ass Is Grass––a text-based series highlighting human impact and consequent environmental phenomena––to X: A Value Not Yet Known, featuring footage captured by Rogers in the rapidly deteriorating Arctic, current themes are explored with a perspective that is at once tantalizing, unsettling, and magnetically visceral.

Perhaps most compellingly, Rogers’s advocacy of the natural world excels in achieving dialectical efficacy without sacrificing nuance. Visible in the jocular antagonism of R.I.P. and the cunning dialectics of Eat Me, Rogers’s work invites the viewer to reenvision a rapidly evolving world, and our role within it.

The World Is Your Oyster

[Two-Channel Video, 2020]

Coalescing the visceral and ephemeral, violent and sensual, The World Is Your Oyster offers a provocative meditation on totality, [d]evolution, and the anthropocene. Presented in two-channel video, the work explores various manifestations of the oyster and other mollusks––life, harvest, cultivation, consumption––against a visual/aural dynamic at once discordant and hypnotic. Contraposing the multi-layered, precious, and luminescent pearl with slicing, shucking, prodding, extraction, and torrents of colorless blood, the project is, like its subject, at once lurid and intimate, vividly organic and exquisitely orchestrated.

In both concept and execution, this work engages with the artist’s GODOG series, most notably the Pussy Buddha. At the onset, she appears both on screen and facing a screen, straddling a patch of shoreline riddled with shells. In this interstitial space between ocean and land, artificiality and nature, she observes the surgical insertion/manipulation of oysters to create pearls. Both voyeur and voyeurized, she mediates between the viewer and image, serving as both spectator and gateway into a profusion of lusciously juxtaposed footage.

Rife with connotations of sensuality, sanctity, and invasion, the oyster has long been associated with the erotic. Works of art from Boticelli’s The Birth of Venus to Steen’s The Oyster Eater portray the oyster as a symbol of lust, pleasure, opulence, and indulgence. Traditionally evocative of the feminine, oysters are naturally protandric, or sequentially hermaphroditic, shifting gender from male to female over the course of their lives. This fluidity underscores a more evolved conceptualization of gender and nature, with nuanced implications for the pearl’s status as a symbol of divinity and transcendence.

Emblemizing purity, fertility, and hidden or sacred knowledge, the commercial pith of the oyster––the pearl––has been harvested and cultivated for millenia. Despite being a symbol of incorruptibility, the pearl’s inception hinges on corruption: the introduction of an irritant into the body of the oyster. This invading object can be organic or inorganic: a parasite, a particle, the oyster’s own eggs, or, as implemented by 12th century pearl farmers, even images of the Buddha. This element of intrusion––and the collision of idolatry and industry––mirrors the history of cultivation. Like many aquacultural creatures, the oyster is prized but also habitually compromised for its delicacy. An image of both sex and death, oysters are both an aphrodisiac and carriers of Vibrio vulnificus, the world’s most deadly seafoood-borne pathogen, killing up to one in five of those afflicted. Holding these elements in tension, The World Is Your Oyster calls to mind the explicit contrast of luxurious excess and bleak commoditization in Mika Rottenberg’s NoNoseKnows, but veers toward implicating the viewer in the pleasure and violence of consumption.

Bookending the Pussy Buddha’s immanence/transcendence, the video concludes with side-by-side footage of a perfect, symmetrically reflected golden pearl and the plunder of the ocean floor. This final juxtaposition recalls Bill Viola’s Nantes Triptych, in which birth and death are laterally positioned, mediated by a suspended, floating human in an interstitial void. Here, likewise, the viewer of The World Is Your Oyster finds herself: suspended between perfection and annihilation, creation and destruction.

As conflictual as it is compelling, The World Is Your Oyster is ultimately a work of excision, at once violating and seductive, ravishing in all senses, all-consuming and offered up for consumption. At the center of these contradictions, the viewer is present as a literal embodiment of the anthropocentric. Whether transfixed, revulsed, or seduced, the viewer’s experience is inevitably one of implication, engagement, and complicity. The world is, after all, your oyster.

The World Is Your Oyster

[Painting, 2020]

Acrylic and Oil on canvas

96 × 216”

In a lush, vivid comingling of poison and pleasure, The World Is Your Oyster offers a sprawling vision of life and death, sex and danger, portent and paradox. Conceived and executed under the condition of worldwide pandemic, the work is at once fragmentary and cohesive, presenting a rich dynamic of conflict, indulgence, and inexplicable harmony.

The most beautiful things can often kill you. Illustrating this paradigm, human forms are spliced and intercut with a variety of natural forms, all of which are potentially lethal: the poisonous pitohui bird; the amygdalin-laced apricot; the highly toxic yellow dart frog; the aptly named ‘murder hornet’; the fatally urushiol-laden unprocessed cashew nut; the wild mushroom, alternately utilized as medicine, hallucinogen, and poison; the fatally intoxicating buttercup; the lovely but venomous cone snail; and the oyster, obsessively hoarded during the 1918 influenza epidemic, at once a carrier of the symbolically sacred pearl and the most deadly seafood-borne pathogen on earth. Optically spherical pearls emblemize nature, industry, and a multiplicity of ideals, while the Venetian grotto chair, artfully modeled after the scallop shell, offers a rich symbol of eroding civilizations and the ubiquity of the Anthropocene.

In the vivid sprawl between the two grotto chairs, the pearl alternately serves as an absorptive presence, a surface for lounging, a recurring object that appears to have been either delicately placed or casually strewn, and hovering above a Venus-like torso in lieu of a head. The span of the painting itself seems to exemplify the interstitial locus inhabited by shells and pearls, an area that is neither life nor death, ocean nor land: a richly shifting present between varied histories and imagined futures.

The work notably interacts with Rogers’s GODOG series, comprised of sculptural, material, and video art highlighting diverse identities and the evolution of gender. Figures such as the playful, provocative Pussy Buddha, a languorous reimagining of the classical Sleeping Hermaphroditus, an androgynous dual-faced angel, and incarnations of phallic fetish figures appear in various states of candor and poise, mourning and bliss, isolation and connection.

Aesthetically redolent of the vibrant, imaginative world-building of Hieronymus Bosch, The World Is Your Oyster conjures a wonderland of contradictions. Even the dominant color, a reinvention of chrome yellow pigment––a highly toxic favorite of Van Gogh’s––has historically been used to signal both danger and the divine, and was once culturally heralded as the color ‘associated with all that was bizarre and queer in art and life.’ Encapsulating a myriad of perceptions, The World Is Your Oyster invites the viewer to a world at once edenic and bewildering, rife with things that fester and flourish, harm and delight––a garden of light and beauty that might very well kill you.

She Sells Seashells by The Seashore

[Painting, 2020]

With evocative vibrance and subtlety, a series of paintings by artist Fawn Rogers explores the interplay between presence and absence, obsolescence and isolation, evolution and extinction.

Strikingly hand-painted against vivid monochromatic backgrounds, each painting highlights the grotto chair, a potent symbol of both human invention and the natural world. Fabricated in Venice––a city whose gradual descent into the sea is itself a reminder of the transience of human civilization––the chairs appear as both lonely and luxuriant, a recollection of the chair’s history as reserved for royalty. In a remarkable progression from obscurity to ubiquity, the chair is rarely mentioned in antiquarian texts (the Bible makes no reference to chairs, despite copious references to thrones), and Shakespeare utilizes the chair predominantly as a symbol for royal claims and personages. Instated as an object of opulence in ancient Egypt, the chair surged in production and use during the 18th and 19th centuries, a shift reflected in literature and exemplified by the shell-inspired aesthetics of Rococo design in the 1700s.c.

With aesthetics that bridge the sculpturally ornate and the darkly cadaverous, She Sells Seashells by the Seashore recalls the architecturally structured, high-contrast photographs of Ruth Bernhard, including such works as Shell in Silk and Banded Murex Deep Sea Scallop. Both visually and historically, there is a spectral dynamic to the beauty of an empty shell. The scallop shell serves as a symbol of rebirth in Christianity, as well as a pre-Christian Celtic symbol of death. In the 19th century, Oliver Wendell Holmes identified the empty shell as a symbol of the human soul passing into eternal life. This interstitial space between life and death is reinforced by the natural habitat of the seashell: a setting that is perpetually suspended between water and land, wilderness and civilization.is innate to the morphology of the shell.

Inspired by the scallop, the grotto chair makes an appearance in several of Rogers’s works, including The World Is Your Oyster and the GODOG series. In these works, mollusks and their shells recurrently emblemize the diverse conflicts and collusions among nature and industry.

Etymologically, the root of scallop derives from *skel-, meaning to cut. In a significant twist of meaning, this linguistic heritage is shared with both skeleton and sculpture––things at once powerful and delicate, the height of nature and art, yet doomed to outlast the bodies and cultures they inhabit. An empty scallop shell once contained––and was created by––the life inside it. Likewise, the empty grotto chair captures the height of beauty and creation, as well as their inevitable loss.

In its melancholic depiction of a single empty chair––and an aesthetic tendency toward rich textures and amorphous lines––the work calls to mind Van Gogh’s paintings Gauguin’s Chair and Vincent’s Chair, conveying both humanity and profoundly felt absence. In Rogers’s depictions, the chair often appears as both exquisite and forlorn, a balance underscored by the hauntingly repetitive dynamic of the series. Redolent of the mass production of chairs during the Industrial Revolution, this repetition also conjures the dreamlike, elegiac contrasts present in Andy Warhol’s Shadows series.

Despite the visual absence of human figures, the element of humanity is deeply conveyed in absentia. Rogers’s notes: “Viewers often express a visceral longing to see someone in the chair. The absence of a human figure creates a question, a sense of incompletion and speculation.” With an approach both historically grounded and keenly prescient, She Sells Seashells by the Seashore offers a meditation on opulence and fragility, ubiquity and seclusion: creation and curation as human artifact.

Homage to Bosch, 2020

Oil on canvas

24 × 30'“

Fukushima Soil, Meteorites, and the Lipstick

[Sculptures, 2013/2019]

Size: 12.5 x 8x8” - 12.5 x 8 x 7.5” - 12.5 x 8 x 7.5”

Resin, Fukushima soil, meteorites, lipstick, et al.

Encasing an eclectic series of objects in octagonal prisms of resin, Fawn Rogers provides future viewers with evidence of life in the volatile present. Featured elements range from meteorite fragments to volcanic residue to an evocative tube of lipstick: a gamut of symbols centered on explosions of every kind, whether cosmic or orgasmic, manmade or natural, from the earth or from the sky. The resin shapes are molded from naturally occurring formations of crystallized lava. Each object seems to float in the translucent material, suspended in a permanent state of dynamic disarray. Particles are dispersed as if carelessly or violently thrown, a gesture hovering somewhere between randomness and intention.

Rogers seems to revel in juxtaposing the cosmic scale with the individual and particular, pitting the politically significant against the ostensibly trivial. The materials ensconced in the work reflect this dissonance, highlighting eruptions and bursts produced by manmade processes, the natural world, and the solar system. Alongside the lipstick and meteorite, she includes soil from Fukushima, a smartphone, GMO corn, a marijuana joint, and teeth whitener. Rogers understands the potential of objects to bring about explosive change––both literally and figuratively––with infinitely complexifying ripple effects. With a light but provocative touch, Fukushima Soil, Meteorites, & the Lipstick attests to the undeniable interconnectedness of everything in existence.

In Rogers’s studio, collected and labeled like the specimens of a meticulous naturalist, are materials she will include in future iterations of this work. They include objects as diversely resonant as patented Monsanto corn, samples of terra preta (the most fertile soil in the world), seed smuggle books (used to illicitly transport heirloom seeds in defiance of international law), lynx fur, Timex watches, and rose bush thorns. Concerns for ecology, biodiversity, and sustainable forms of life and agriculture recur in these choices, as they do throughout Rogers’s practice. While she foregrounds the effect human beings have on the planet, her work also reflects a cognizance that we are inextricably part of the natural world. The watches, joints, and cosmetics speak to the passing of time, and to the human desire for youth, pleasure, and beauty. These objects are also souvenirs of our existence, just as the fur tufts are evidence of the lynx.

It would be easy for a conceptual description of the work to neglect its striking beauty. The objects lying frozen within their cloudy masses are only partially visible. Items are at once preserved and distorted by the volcanic shape, which functions simultaneously as artwork and plinth. Numerous works can be stacked on top of each other to create a unique and formidable totem that contains the past and present with an eye toward the future. Both visually nebulous and inflexibly archival, these are time capsules that subtly embody the mystery of the circumstances that might find them. The natural world, though indelibly affected by its human constituents, will survive our impact and continue to evolve.

Yes, Yes It Is Burning Me

[Two-Channel Video, 2019]

Courtesy of Dakis Joannou

Filmed in a variety of locations on Hydra Island, Greece, Yes, Yes It Is Burning Me is a dual-channel video installation exploring humanity’s complex relationship with the natural world. The title of the installation is a response to the questions posed by a monk at a local monastery: “Is the stone warm from the sun? Can you feel it? Do you like it? Does it go all the way down your body as you hold it?” Combining rich visual elements and natural sounds recorded on the island, Yes Yes It Is Burning me centers on the conveyance of rocks, a representation of all matter, as a symbolic focal point.

Through a series of symbolically lush vignettes, the viewer observes the repetitive movement of stones. These objects take on a variety of interpretations, spanning a diverse spectrum of contexts and human interactions. The visceral narrative journeys through towns, farms, beaches, a boat graveyard, a monastery, a casino, and the Deste Foundation’s Slaughterhouse project space. From strangers and local villagers to the artist herself, the video’s human participants exist within an unidentifiable moment in time, illustrating a universal preoccupation with purpose, meaning, and motion detached from progress.

The video begins with a naked woman, Rogers herself, walking with a horse and baby mule. Ostensibly indicative of freedom and innocence, the harmonious scene is disrupted by the harsh, gradually revealed reality of them walking on a bed of trash against a backdrop of abandoned boats. In a more contemporary setting, Rogers is observed sleeping, intercut with footage of an abused donkey eating thorns and stones as a man wearing a saddle walks behind. Linking these scenes, images of subjugation and entropy are juxtaposed with moments of the artist meditatively, repetitively stacking rocks.

In a later time-lapsed scene, spanning the day’s course from sunrise to sundown, a local monk appears holding a rock. In a disturbingly charged hybrid of indecency and intimacy, the monk slides the rock up and down over the body of the artist as she lies on the ground. During this discomfiting, spontaneous moment of candid molestation––endured but unprompted by the artist––the monk poses the series of questions presaging the work’s title. In a local casino, the same rock is held by a series of individuals, each with a distinct sensation of its heft and import.

Ultimately, the film concludes in a state of play. Clad in a youthful yet danger-redolent yellow, Rogers stacks, throws, and arranges rocks with numbness or bliss, a monotony that recalls Camus’s reinterpretation of the ancient Greek myth: an image of Sisyphus smiling.

Your Ass is Grass

[Mirror Paintings, 2020]

Reflecting––both literally and figuratively––a narrative of chaos and convolution, Your Ass Is Grass traces socio-ecological events with perspicacity and playfulness. The series is comprised of brightly colored, multi-layered paintings on mirror. Combining spectrums of colors in horizontal gradients with what Rogers calls an obscured peripheral shadow, visible only upon an angled view, the series conflates text as image to powerful effect.

The multiple expressions in the series––Your Ass Is Grass, Sunny Day Floods, Polar Vortex, Iceberg, and Woolly Mammoth––each indicate a different phenomenon and a recent introduction to the common vernacular. The first and eponymous work offers a tongue-in-cheek reference to environmental impact as mutually assured destruction, while Sunny Day Floods references the wild sea level fluctuations experienced in Florida, causing city streets to flood on perfectly sunny days. Popularized by bizarre winter weather patterns in Chicago, Polar Vortex invokes the violent storm systems exacerbated by global temperature shifts, and Iceberg offers a companion piece, bringing to mind both dissolving floes and massive hazards of disruption, like furniture discarded on the side of the road. Lastly, Woolly Mammoth is fraught with radical implications, conjuring not only the majestic and famously extinct creature, but also cloning technologies’ current efforts to raise it from the dead before the ice in the Arctic fully melts.

As is true throughout Rogers’s oeuvre, ecological themes are treated with dark humor, accounting for an expansive view of nature and industry. This is perhaps most salient in Rogers’s video art, such as X: A Value Not Yet Known and The World Is Your Oyster, but also perceptible in the sumptuous, circular aesthetics of Yes Yes It Is Burning Me. Rogers’s predilection for second-person present tense underscores the impression that the viewer is complicit. Each in its own way, Rogers’s paintings and installations seem poised to disturb and delight, inviting the viewer into the pleasure/pain of [dis]comfort.

Prizing dimensionality and play, Your Ass Is Grass shares a kindred spirit with Doug Aitken’s text sculptures, as well as the literally electric text art of Tracey Emin. There’s also a streak of the dark humor found in Ed Ruscha’s text paintings, a tonally apt approach to themes ranging from resuscitating the long-extinct mammoth to surviving our own human-induced environmental disasters. Confronted with bold, blinding text directly at eye level, the viewer can’t help but feel implicated by the message: Your Ass Is Grass.

X: A Value Not Yet Known

[Two-channel video, 2019]

Courtesy of Philip Niarchos

Rogers’s X: A Value Not Yet Known begins with a rhythmic waltz, as a camera pans over the Arctic Sea. The ice floes with jagged edges disconnect from one another, revealing the sensuous and inky black water between. The music is punctuated by the orgiastic sounds of a couple as the lens focuses onto the pure and clear blue of an iceberg––a naturally formed X shape filling the entirety of the frame. This shape is echoed in title and meaning throughout the film, a representation of the mathematical symbol of something that remains unknown, something to be found. An equation is postulated. The parts are composed of a polar bear, now in unknown territory; a parade of woolly mammoths, recreated for a possible future; and a golem-like figure, the human, burdened by an endless river of technology and materialism represented by the silver material within which it is bound.

Throughout the video piece, Rogers connects the body with nature. As one hears the sound of a couple in ecstasy, we are made aware, through the exquisite shots of the blue ice and dark waters, of the danger that lies within. Rogers compels us to stand firmly footed in the Anthropocene. She mixes time signatures: the human and the earth’s, engaged in a simultaneous but divergent dance.

This is not to say that Roger’s work is fundamentally an ecological proclamation, but rather the documentation of a process that is occurring at the sum of the Anthropocene. The film captures the silent cracking of the ice floe while metallic insect sounds fill the void of their breaking.

A voice echoes, “An ocean of, and an ocean of,” each falling somewhere between the What Has Been and What Will Be, the heart-wrenchingly human and the universal. “An ocean of lost hopes. An ocean without time.” There is a sense that the dark waters below the ice have become the primordial ooze from which life spawns––it is the seminal fluid, the psychosexual oceanic consciousness exposed.

The voiceover continues, now female, as an omnipresent force within the video. “I love your bones, and your blood, and your bile, I love the shape of your organs, and the dark brown color of your liver...” The narration’s barely audible whispers describe the evisceration of a body, an amorous moment with the organs, the systemic qualities, its color, shapes, and power. As the body dissolves to its hidden parts through violent description, the space before the camera is connected. It is through the human interaction that the pitch-black liquid pours forth. A violence against the earth that is enacted through human interaction alone. The greed and the blatant disregard for the future is captured through the ancillary video piece Run, Run. Featuring an endlessly turning gilded rat wheel, it is pushed forever forward by an invisible force, an irregular rhythm. Its quick movement with the inevitable slowing, magically, effortlessly, and just shy of randomly, is soundlessly perpetuated.

Three CGIed woolly mammoths in a single military formation crossing the landscape become heroic figures. Despite being CGI representations, these mammoths are the harbingers of an inevitable conclusion. Juxtaposed with their purposeful gait is the now-emaciated polar bear eating from a trashcan. The ghostly digital representations of the behemoths recall scientific efforts to combat the approaching climate disaster through the reviving of the long dead beast. Scientists posit their grazing on the Arctic tundra will expose the earth underneath to the cold air. The refreezing of the dirt beneath the vegetation is one of the planet’s last resorts to maintain the balance of the frozen poles. Earth’s future will continue through the ancient black blood of mammoths preserved below the ice.

In the final scene, an anonymous figure, golem-like, unfurls and rises from the newly exposed soil. The petrichor inhaled by Rogers’s abstracted body maintains a hopeful vision. Its metallic blanketing reflects the sky above onto the ground below. The earth and cosmos collapse upon themselves, falling into symmetry. The visceral nature of our experience, the conflation of hominid and earth, and the folding of time are all wrapped within the faceless body of our future.

R.I.P.

[Installation, 2016]

The game of chess, originally conceived during the 6th century C.E., has survived and evolved for nearly 1500 years, an enduring artifact of strategy, competition, and domination. Coalescing the elements of play and seriousness, the game of chess has long been admired as a bastion of logic and order, but it is, at its core, a game of war, predicated on machinations of violence and obliteration. Capturing this irony as an irresistible emblem of the Anthropocene, Rogers’s reenvisioning of the game in R.I.P. configures independent actors in the classic formation, but with the traditional royal figurines replaced by regal sculptures of animals: six creatures who have recently become extinct.

Positioned on an oversized, dual-tone chess board crafted from wenge and white oak, 16 individual animal sculptures appear in high-polished bronze with a classic patina, facing a mirroring team of 16 sculptures in sand-blasted bronze with a black patina. As is characteristic of Rogers’s work, the animals are presented with both elegance and a touch of humor, imposingly dignified yet rife with personality. Each piece reflects a detailed, organic aesthetic that belies the pieces’ material weight and solidity. The result is a series of figures that are both mournfully static and exquisitely lifelike.

Often considered the first casualty of Anthropocene expansion, the Great Auk appears as the bishop. The last known egg of the species was destroyed in 1844, crushed underfoot by Icelandic sailors in their rush to capture its parents. The Pyrenean Ibex, whose 2000 extinction was followed by a flurry of cloning efforts (producing, for a few minutes prior to its death, a live incarnation in 2003), appears as the knight. A small army of intently forward-looking frogs serve as pawns and, in a sly reference to the extinction of half the world’s amphibians, comprise half the pieces on the board. The Western Black African Rhino, excessively poached for the magical/medicinal contents of its horn, stands as the rook. A majestic Cape Lioness, her expression bent in a defiant near-snarl, appears as the queen, while the Mexican Brown Bear, historically decimated by the same conquistadors who colonized North America, serves as the king.

Chess is a game of triumph, but triumph is a corollary of conquest. It is, notably, a game the Buddha refused to play. The game’s colonial history––traceable from ancient India to the Muslim world to imperial civilizations in Europe and northern Asia––coupled with an emphasis on dominance, finds fresh implications in the contemporary subjugation of the natural world. Even the historical styles of chess––Romantic, Scientific, Hypermodern, and New Dynamism––alludes to shifting cultural values and power structures, concluding, perhaps, with the game’s association with technology and artificial intelligence.

Chess has long held a place of fascination for artists, from Matisse to Man Ray, Duchamp to Paul Klee, and beyond. Engaging in this legacy, Rogers repurposes a familiar form to uniquely compelling ends. In its prescient entanglements of order and chaos, civility and savagery, R.I.P. presses past a playful exploration of anthro-ecological history and evades purely dogmatic, observational, or elegiac orientations. The viewer becomes a player, autonomous yet complicit: a participant in the Anthropocene, at once a witness and contributor to a legacy of humanity, immortalization, and extinction.

Eat Me

[paintings, 2020]

Eat Me, 2020

Acrylic on smoked oyster and sardine boxes

11.5 × 17“

Eat Me, 2020

Acrylic on smoked oyster

and sardine boxes

11.5 × 17“

Eat Me, 2020

Acrylic on smoked oyster

and sardine boxes

11.5 × 17“

Eat Me, 2020

Acrylic on smoked oyster

and sardine boxes

11.5 × 17“